About the Author: Scott Barry Kaufman is a cognitive psychologist investigating the development of intelligence and creativity. His latest book is Ungifted: Intelligence Redefined. Follow on Twitter@sbkaufman.

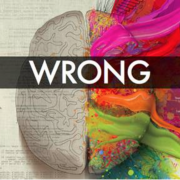

So yea, you know how the left brain is really realistic, analytical, practical, organized, and logical, and the right brain is so darn creative, passionate, sensual, tasteful, colorful, vivid, and poetic?

No.

Just no.

Stop it.

Please.

Thoughtful cognitive neuroscientists such as Anna Abraham, Mark Beeman, Adam Bristol, Kalina Christoff, Andreas Fink, Jeremy Gray, Adam Green, Rex Jung, John Kounios, Hikaru Takeuchi, Oshin Vartanian, Darya Zabelinaand others are on the forefront of investigating what actually happens in the brain during the creative process. And their findings are overturning conventional notions surrounding the neuroscience of creativity.

The latest findings from the real neuroscience of creativity suggest that the right brain/left brain distinction is not the right one when it comes to understanding how creativity is implemented in the brain.* Creativity does not involve a single brain region or single side of the brain.

Instead, the entire creative process– from preparation to incubation to illumination to verification– consists of many interacting cognitive processes and emotions. Depending on the stage of the creative process, and what you’re actually attempting to create, different brain regions are recruited to handle the task.

Importantly, many of these brain regions work as a team to get the job done, and many recruit structures from both the left and right side of the brain. In recent years, evidence has accumulated suggesting that “cognition results from the dynamic interactions of distributed brain areas operating in large-scale networks.”

Depending on the task, different brain networks will be recruited.

For instance, every time you pay attention to the outside world, or attempt to mentally rotate a physical image in your mind (e.g., trying to figure out how to fit luggage into the trunk of your car), the Visuospatial Network is likely to be active. This network involves communication between the frontal eye fields and the intraparietal sulcus:

If your task makes greater demands on language, however, Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area are more likely to be recruited:

But what about creative cognition? Three large-scale brain networks are critical to understanding the neuroscience of creativity. Let’s review them here.

Network 1: The Executive Attention Network

The Executive Attention Network is recruited when a task requires that the spotlight of attention is focused like a laser beam. This network is active when you’re concentrating on a challenging lecture, or engaging in complex problem solving and reasoning that puts heavy demands on working memory. This neural architecture involves efficient and reliable communication between lateral (outer) regions of the prefrontal cortex and areas toward the back (posterior) of the parietal lobe.

Network 2: The Imagination Network

According to Randy Buckner and colleagues, the Default Network (referred to here as the Imagination Network) is involved in “constructing dynamic mental simulations based on personal past experiences such as used during remembering, thinking about the future, and generally when imagining alternative perspectives and scenarios to the present.” The Imagination Network is also involved in social cognition. For instance, when we are imagining what someone else is thinking, this brain network is active. The Imagination Network involves areas deep inside the prefrontal cortex and temporal lobe (medial regions), along with communication with various outer and inner regions of the parietal cortex.

Green= The Executive Attention Network; Red= The Imagination Network

Network 3: The Salience Network

The Salience Network constantly monitors both external events and the internal stream of consciousness and flexibly passes the baton to whatever information is most salient to solving the task at hand. This network consists of the dorsal anterior cingulate cortices [dACC] and anterior insular [AI] and is important for dynamic switching between networks.

The Neuroscience of Creative Cognition: A First Approximation

The key to understanding the neuroscience of creativity lies not only in knowledge of large-scale networks, but in recognizing that different patterns of neural activations and deactivations are important at different stages of the creative process. Sometimes, it’s helpful for the networks to work with each other, and sometimes such cooperation can impede the creative process.

In a recent large review, Rex Jung and colleagues provide a “first approximation” regarding how creative cognition might map on to the human brain. Their review suggests that when you want to loosen your associations, allow your mind to roam free, imagine new possibilities, and silence the inner critic, it’s good to reduce activation of the Executive Attention Network (a bit, but not completely) and increase activation of the Imagination and Salience Networks. Indeed, recent research on jazz musicians and rappers engaging in creative improvisation suggests that’s precisely what is happening in the brain while in a flow state.

However, sometimes it’s important to bring the Executive Attention Network back online, and critically evaluate and implement your creative ideas.

Or else this can happen:

As Jung and colleagues note, their model of the structure of creative cognition is only a first approximation. At this point, we just have leads on the real neuroscience of creativity. The investigation of large-scale brain networks does appear to be a more promising research direction than investigating the left and right hemispheres; the creative process appears to involve the dynamic interplay of these large-scale networks. Also, converging research findings do suggest that creative cognition recruits brain regions that are critical for daydreaming, imagining the future, remembering deeply personal memories, constructive internal reflection, meaning making, and social cognition.

Nevertheless, much more research is needed that investigates how the brain creates across different domains, species, and timescales.

It’s an exciting time for the neuroscience of creativity, as long as you ditch outdated notions of how creativity works. This requires embracing the messiness of the creative process and the dynamic brain activations and collaborations among many different brains that make it all possible.

© 2013 Scott Barry Kaufman, All Rights Reserved link to <http://www.scottbarrykaufman.com/>

Disclaimer: I was one of the reviewer’s of the paper by Rex Jung and colleagues.

Note: For more on the latest findings in the emerging neuroscience of creativity, I highly recommend the recent book “Neuroscience of Creativity,” edited by Oshin Vartanian, Adam S. Bristol, and James C. Kaufman.

* There’s some grain of truth to the left brain/right brain distinction. For instance, spatial reasoning recruits more structures in the right hemisphere, and language processing recruits more structures in the left hemisphere. Also, there’s some really interesting research conducted by John Kounios and Mark Beeman showing that the Aha! moment of insight– in which participants discover seemingly unrelated words– is associated with activation of the right anterior superior temporal gyrus. None of these findings, however, negate the fact that the entire creative process involves the whole brain.

image credit #1: io9; image credit #2, 3, & 5: findlab.stanford.edu; image credit #4:pnas; image credit #6: photocase

This article originally appeared at Scientific American http://www.creativitypost.com/science/the_real_neuroscience_of_creativity#sthash.G9QeG9D9.dpuf