Psychology of Hate

We are experiencing an increasing level of hate in our society. Hate fuels the cancerous divisiveness and polarization which now infect virtually every part of our lives. This culture of hatred will have serious effects on both our national and individual emotional, psychological, and physical health.

We cannot be a strong and healthy nation if we consider hate an acceptable aspect of our daily life. Hatred has the destructive power to permanently damage the nation’s emotional psyche and core values.

History tells us how hate can be exploited to lead an entire nation to commit unspeakable crimes against a particular racial, religious, political, or ideological group.

It is time to sound the alarm.

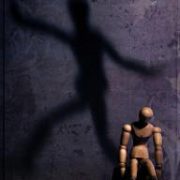

The problem is we know very little about the nature and workings of hate and what we as a people can do about it. While anger can be resolved and fades with time, hate at its extreme is an enduring, inflexible state, an all- consuming set of raw emotions.

If hate is left unchecked, it intensifies from intolerance to a wish to annihilate the other. Hate strips us of our humanity. Hate eliminates the ability to show empathic concern for the injustice done to others. Hate numbs the guilt and shame that we should feel for our prejudiced behavior. Most importantly, it eliminates our ability to understand why we feel this hatred and how to eliminate it by addressing the real issues that gave rise to it.

It strikes at the core of our humanity.

People who hate tend to think, feel and behave from an “in-group” versus an “out-group” mentality. They have no hesitation to stereotype an entire “out-group” (Steward, T. L. et al., 2003). The “ins” use the “outs” as scapegoats for the social, economic, and political woes of the community (Brewer, M., 1999). The “ins” use this as a way to justify the treatment of the “outs” in a degrading manner and to ostracize the “outs” from the lives and the community of the “ins”. In her blue eyed and brown eyed study, Elliot et al., 2002 showed that when the blue eyed subjects were severely discriminating and degraded them and made to feel like outer groups in society, it was too much for some that they left the study.

The underlying insidious presence of contempt and disgust – a deep dislike for the other who is considered unworthy of respect or attention – appears to play a major role in intensifying fear and anger into a vicious, annihilating feeling of hate. Disgust of another instinctively makes us recoil and distance us from them (Taylor, K, 2007). Contempt is a disdain associated with the other being less worthy and inferior and, therefore, not entitled to certain rights and opportunities that are reserved exclusively for the “ins” (Sternberg, R.J. 2017).

——-

Extreme hate, unfortunately is deep seated and cannot be easily overcome. For people whose hate is not all-consuming, here are some preliminary steps that might be helpful for decreasing hatred in our lives.

The first step is to understand that hate is extremely destructive, whichever way you cut it, by recognizing the serious threat that hate creates for our personal, communal, and national well-being.

Next, learn to spot stereotyping, scapegoating, and de-humanizing behavior in ourselves, in others, and in certain leaders, so that we can start challenging such prejudiced verbal and non-verbal behavior.

The unravelling of the sexual misconduct of Harvey Weinstein has created a collective outrage in society and put in place an entirely new set of norms. The same opportunity exists for us to do this with hatred and hate mongers.

So, when you find yourself blaming an entire group, challenge that perception by conducting a comprehensive analysis of your behavior. What is the evidence that the “outs” are responsible for a particular situation or for the acts of a few?

While reducing prejudiced behavior is a great start, reduction alone does not prevent such behavior from returning. The change in our behavior as a society can only be sustained if we challenge the underlying beliefs and assumptions that maintain this toxic behavior.

Make a list of evidence for and against your own beliefs and assumptions. Based on the conclusion of the analysis, replace your maladaptive beliefs and assumptions with ones that are more realistic and adaptive.

To go deeper, ask yourself what are the origins of such beliefs? Try recalling the earliest time in your life when you experienced hate towards a significant person? It won’t take long to figure out how these unprocessed feelings are projected to the out-group.

Now that you know that your beliefs and assumptions about the “outs” may be biased, take concrete steps to re-educate yourself by reading and watching objective based information. Evaluate the issues from the viewpoint of both sides – don’t just listen to what you would like to hear from CNN or Fox alone.

If you want others to hear and to understand your legitimate grievances, you must also understand theirs. Reach out to members on the other side and genuinely listen and try to appreciate their perspective by putting yourself in their shoes. The capacity to do so will allow you to change your beliefs where you are misinformed or wrong.

Each one of us needs to initiate change in our own behavior before we can expect society to change.

In a democratic system such as ours, holding opposing beliefs and views is not the real issue. The problem is intolerance and feelings of outrage at the “outs” with little regard for their rights, which are protected by the constitution – as are your own rights. Our system provides the ballot box, the judiciary, and the legislature, which relatively few nations in the world enjoy, as the final place to settle our concerns and differences.

It, therefore, behooves us to make a resolution to reclaim our humanity and not allow ourselves to be caught in the whirlwind of hate being spewed in our country.

Lobsang Rapgay, PhD is a Sherpa-Tibetan American and Assistant Adjunct Professor, and researcher in the Department of Psychiatry UCLA. He has a private practice specializing in the treatment of anxiety disorders.