The Roots of Eudaimonia: An Interview with Dr. Joseph Raho

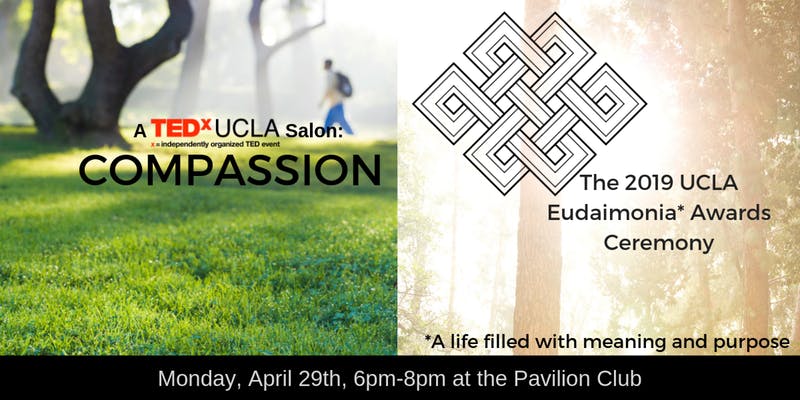

UCLA is holding their third annual Eudaimonia awards on April 29th, 2019, and in anticipation for the event, I sat down with ethicist Dr. Joseph Raho to discuss the roots of eudaimonia in ancient Greek philosophy. After majoring in philosophy in undergrad, Dr. Raho wished to use the analytic skills he learned during his studies in a very practical way. He found that opportunity in bioethics, landing a job after graduation with The President’s Council on Bioethics (a federal bioethical commission in DC). That experience led him to pursue his PhD in moral philosophy with a concentration on end-of-life ethics at the Universita’ di Pisa, Italy. This is how Dr. Raho ended up living in Italy for five years, developing a passion for Italian art and culture, espresso, and reminiscing about the passeggiata. He returned to the States to do his post-doctoral fellowship in clinical ethics at the UCLA Health Ethics Center in 2014. He was hired as clinical ethicist for UCLA Health in the spring of 2016. In this role, he aims to facilitate the principled resolution of ethical conflicts and challenges that healthcare professionals, patients, and their families face in the hospital setting.

UCLA is holding their third annual Eudaimonia awards on April 29th, 2019, and in anticipation for the event, I sat down with ethicist Dr. Joseph Raho to discuss the roots of eudaimonia in ancient Greek philosophy. After majoring in philosophy in undergrad, Dr. Raho wished to use the analytic skills he learned during his studies in a very practical way. He found that opportunity in bioethics, landing a job after graduation with The President’s Council on Bioethics (a federal bioethical commission in DC). That experience led him to pursue his PhD in moral philosophy with a concentration on end-of-life ethics at the Universita’ di Pisa, Italy. This is how Dr. Raho ended up living in Italy for five years, developing a passion for Italian art and culture, espresso, and reminiscing about the passeggiata. He returned to the States to do his post-doctoral fellowship in clinical ethics at the UCLA Health Ethics Center in 2014. He was hired as clinical ethicist for UCLA Health in the spring of 2016. In this role, he aims to facilitate the principled resolution of ethical conflicts and challenges that healthcare professionals, patients, and their families face in the hospital setting.

Photo by Julia Saltzman

Q: If you had to give a quick elevator pitch to describe Eudaimonia to someone who did not know what it was, what would it sound like?

A: I would have to start with what it means in Ancient Greek: Eu (good) daimon (divinity or spirit). It’s someone who has a good spirit, or someone who has been able to realize their inner spirit. In English, it’s something akin to happiness, enjoyment, or pleasure. The best translation is not happiness, however, but a state of flourishing or excellence. Aristotle connected eudaimonia with virtuous behavior—virtue in accordance with reason and contemplation. Virtue is not about singular, isolated activities and behaviors, but habitual ones. You become virtuous by molding yourself through your actions over time. This raises important questions: What does it mean to be human? What does it mean to flourish specifically as a human being? What does it mean to live well? What kind of person do I desire to become? What kind of activities, projects, or hobbies should I seek out because they will be conducive to my overall flourishing? At a very rudimentary level, it will be hard to flourish if you don’t have the basic necessities in life. I would also add that it’s hard to flourish alone—activities, projects, and hobbies are important, but frequently leave one only partially fulfilled, so relationships are a big part of what it means to flourish. To live well involves doing good not only for yourself, but also for others. We must strive to go beyond ourselves, overcoming our limitations. Finally, living a good life is, in a major way, connected with the various roles one has been given or assumed in life (for example, that of a parent, healthcare professional, or teacher). What does it mean to truly flourish in those roles?

Q: Where did you first hear about Eudaimonia? What do you remember about that moment/time?

A: It was my freshman year of college while studying ancient philosophy. I remember that when the professor talked about it, the concept resonated with me. I think each of us tries to live a meaningful existence. Human beings strive to create meaning. It doesn’t necessarily matter what the answer is, it’s about the dialogue—and that really drew my interest.

Q: How do you incorporate Eudaimonia into your life?

A: Mindfulness and reflection about your life and the lives of others.

Q: Can you explain the link between Eudaimonia and Philosophy?

A: The word philosophy comes to us from Greek, meaning “love of wisdom.” Yet, you don’t have to be an academic philosopher to be a reflective thinker. Human beings are naturally curious and reflective individuals. We all yearn for understanding and meaning. Philosophy is a branch of knowledge that tries to uncover fundamental truths about ourselves and our world in a systematic way. Eudaimonia is a state of human flourishing or excellence. Philosophical reflection would seek to better understand fundamental truths about what it means to flourish or be excellent human beings and why.

Q: What’s one bit of advice you would give to someone looking for meaning and purpose in their lives?

A: I would ask the person: “Where do you find joy in life and why is that aspect of your life filled with joy?” Trying to find meaning and purpose in life is admittedly very subjective—it will depend on what a person values. Striving for meaning and purpose should be understood as a journey instead of as a destination. It’s not necessarily about achieving particular things or goals (even if those things are important). Ultimately, I think the person should ask herself “What kind of person do I want to become?” and then strive toward that ideal.

Q: What can one do daily, monthly, yearly, to live with Eudaimonic principles?

A: That is a very difficult question! One should think about what it means to flourish in a holistic sense and set that as a goal for oneself. Then, he or she should strive to live in accordance with that goal one step at a time, recognizing that it may need to be modified along the way.

Q: What gives you purpose in life?

A: Relationships. Being a good partner, a good friend, a good family member, a good colleague. We should also try to help people if we are in a position to do so. Finally, we should be mindful about our actions and their impacts on others. As an ethicist, I aim to identify, analyze, and help people navigate difficult value-laden decisions. My goal is to equip them with the tools needed to arrive at their own decisions, in a way that is consistent with their deeply-held values and beliefs. I like to think that I am using my training in a creative way to assist individuals who may be struggling with complex medical decisions.

Q: What would you like UCLA to know about the Eudaimonia Awards?

A: The purpose of the awards is to recognize outstanding persons whose actions embody our collective ideals of a life well lived. The winners not only excel as individuals, but also use their talents for the broader good of the community and society at large by making an impact on the lives of others. By recognizing and celebrating such excellence, the hope is to get people on campus to think: “That is the type of person I want to become.”

Aubrey Freitas is an undergraduate student at UCLA double majoring in English Literature and Psychology with a minor in Italian. She is a blogger for the Semel Healthy Campus Initiative Center at UCLA in the Mind Well section, which focuses on the importance of mindfulness and mental health. Aubrey is the founder of the organization Warm Hearts to Warm Hands, which teaches the skill of knitting to people of the community in return for their donation of an article of clothing they create with the skill, to be given to local homeless shelters.